Managing swine dysentery in grower finisher pigs

Swine dysentery (SD) remains a global challenge and most often appears in grower finisher pigs where mortality losses and sub-optimal performance can impact pig production. Much like with other diarrhoea-causing bacteria, such as Lawsonia intrecellularis, Salmonella spp, Brachyspira spp, some farms are more susceptible than others and can result in disease. So what’s the solution? From a nutritional point of view, managing the pig’s microbiota ensures that pathogenic bacteria remain dormant.

What is swine dysentery?

SD is caused by the gram negative bacteria Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, which causes extensive inflammation and necrosis of the intestinal epithelial surface of the colon and caecum. The first clinical signs are soft mucoid yellow to grey faeces and anorexia cases. Typically, diarrhoea increases in severity and quickly becomes bloody with excess mucus (mucohemorrhagic). Morbidity can exceed 50%, and when left untreated it can lead to high levels of mortality. Additionally, it results in poorer growth rates and reduced feed efficiency. The incubation period ranges between a couple of days to several weeks, and the bacteria can persist in faeces for several months (depending on moisture and temperature). B. hyodysenteriae enters the pig orally with transmission mainly via faeces. It can also be transmitted by other animal species or animal caretakers. After ingestion, B. hyodysenteriae colonises and proliferates in the colon and caecum. SD requires the presence of other bacteria (like Fusobacteria spp., Clostridium spp. and Bacteriodes spp.) in sufficient numbers.

These bacteria contribute to the penetration of the intestinal mucus layer and attachment to colonic epithelial cells. This results in failure of epithelial transport mechanisms, like active transport of Na+ and Cl- ions from lumen to blood. The end result of colonic malabsorption is diarrhoea.

Swine dysentery in the Netherlands

It is noteworthy that SD has almost disappeared in the Netherlands, with only a few isolated cases reported. The disease is now rarely detected by veterinary health authorities. Over the past 10 to 15 years, SD has gradually faded, and in our view, some key factors have made a significant contribution to this development:

- Strict adherence to hygiene and biosecurity protocols.This applies both in farming operations and in the transport and supply of animals.

- A focus on gut health by stimulating diversity of microbiota and managing faecal consistency. By limiting the use of antibiotics that affect the microbiota on the one hand, and on the other, by carefully selecting feed ingredients with the right fibre fractions and lower protein levels, with a stronger focus on optimal amino acid ratios. Also the use of feed and feed management to control faecal consistency and defecation behaviour

- A focus on other diarrhoea-causing bacteria, such as Salmonella and Lawsonia

Due to feedback and intervention measures implemented by slaughterhouses, including widespread vaccination against Lawsonia (PIA). It is important to note that the decline in SD was already evident prior to the implementation of Lawsonia (PIA) vaccination.

Initial steps have been taken within the European Union to approve a vaccine for protection against SD. However, addressing the root causes remains the foundation of effective disease control.

A good start sets the tone

Managing the microbiota starts during the piglet rearing phase. Protein digestibility has to be optimised in this period and a stable, diverse and resilient microbiota needs to be developed. In other words, the focus should be on feeding the gut. See previous articles about Koudijs’ approach to feeding piglets before and after weaning. Good indicators of healthy piglets include proper defecation behaviour along with good and regular feed intake. Achieving this requires producers to focus on the final weeks of piglet rearing and the start of the growing-finishing period. Ensuring alignment with piglet feed, a transition from high to low copper levels and a transition from highly digestible diets to standard grower-finisher diets are also advised.

Nutritional interventions in grower finisher pigs

- Managing the microbiota in grower finisher pigs involves optimal feeding of the commensal bacteria (i.e. butyrate and lactate-producing bacteria). This results in the production of short-chain fatty-acids (SFCAs), which lower the pH in the colon and create an unfavourable environment for spirochetes, like B. hyodysenteriae. Pluske et al., 1996, showed that specific, highly fermentable fibre fractions, like inulin, chicory pulp or potato starch, are effective in reducing the incidence of SD. A balanced approach is essential however, and fermentable fibre fractions should not be excessively.

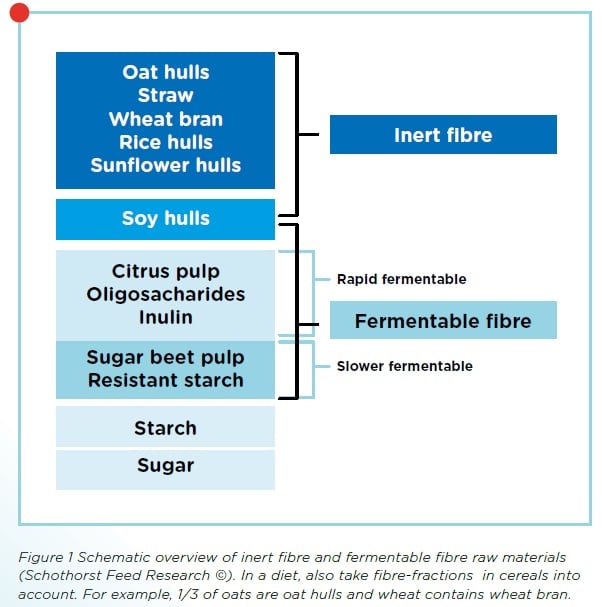

Molist et al., 2009, showed that inert fibres have a positive effect on the microbiota, because they avoid excessive fermentation. These fibres act as physical structure in the gut, contributing to bulk formation and facilitating intestinal transit.

The goal of the nutritionist is to find the optimum level and ratio between fermentable and inert fibres. This is one of the main reasons we use them all in our feed mills (see Figure 1).

To make matters even more complicated and abstract, the optimum level and ratio between fibre fractions also depends on the pigs' feed intake. Including extra fermentable fibres in the diet to stimulate SFCA production is a good option, although care is needed with pigs with a high and irregular feed intake.

- Preventing the formation of a substrate for fermentation in the colon - in terms of starch, glucose and protein – and therefore a substrate for growth of pathogenic bacteria. Use of highly digestible starch sources, like cooked rice, although an expensive raw material in a grower-finisher diet, has been shown to be very effective.

- Addition of enzymes (xylanase and β-glucanase) can support degradation of NSP-fraction.

- Total crude protein content should also be taken into account, with an emphasis on optimising standard ileal digestible (SID) amino acids and their corresponding ratios, in order to avoid excessive protein supply.

- Using organic acids, like lactic acid and formic acid, to reduce the pH in the colon and have antimicrobial effects.

- Keeping particle size in mind. Finer grinding results in improved enzymatic digestion, reducing the amount of substrate available for fermentation in the colon. Coarser particles, however – particularly fibre fractions – support gastrointestinal tract development, and actually stimulate prebiotic effect. Which helps prevent colonisation by certain pathogenic bacteria (i.e. Salmonella) and creates harmless gut microflora with reduced susceptibility to gastrointestinal infections.

How Koudijs can help

Managing swine dysentery starts with a thorough analysis, followed by a well-founded and structured approach: A step-by-step process with monitoring at every stage will ultimately result in good farm performance. We believe in being a hands-on partner who combines practical support with specialised knowledge, shared openly. Backed by an effective product portfolio, our goal is clear: to keep farms running smoothly with minimal disruptions. Talk to a Koudijs representative to find out more.

About the author

Suzanne Hendrikx

Specialist Swine

Do you have any questions or would you like more information? Get in touch with Suzanne.